When the pandemic disrupted every aspect of campus and daily life, the University Libraries responded with innovation and ingenuity.

Carolina’s libraries normally welcome more than 2.6 million people each year. Picture Kenan Stadium filled 45 times over with caffeine-fueled students, world-class scholars and visitors from around the state and the globe.

What happens when some of the most bustling locations on campus meet a pandemic? That’s easy. They stay open virtually, transforming nearly overnight the way they do business.

In 2020, COVID-19 upended every aspect of campus operations, causing Carolina to send students home abruptly in March, resume on-campus teaching in August and then pivot almost entirely back to remote instruction just days into the semester.

In the face of so much disruption, the staff of the University Libraries responded with innovation and ingenuity to help Tar Heels keep teaching, learning and researching.

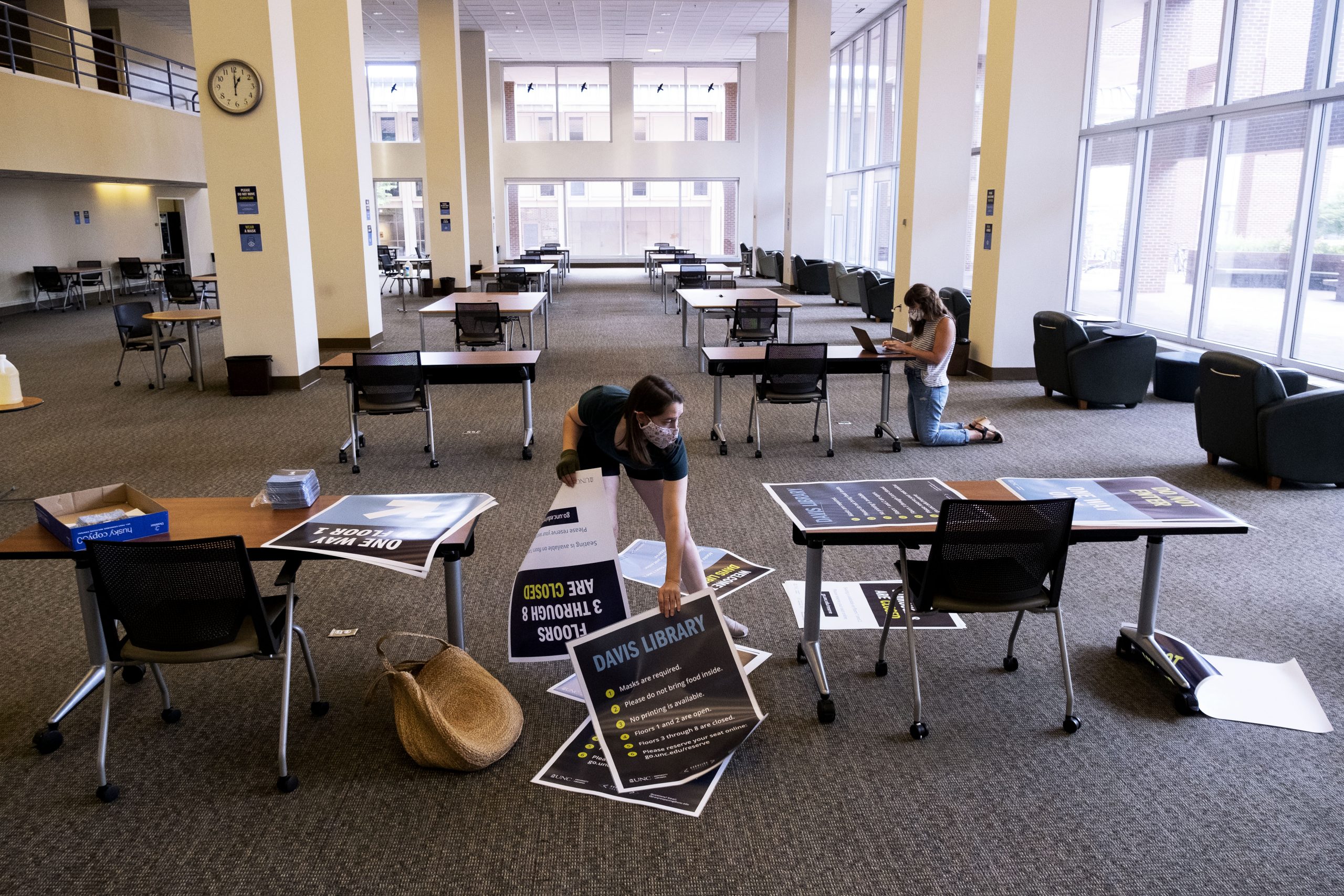

Multimedia and Visual Communications Specialist Aleah Howell readies Davis Library with new COVID-19 signage and seat reservation labels. July 28, 2020.

(Jon Gardiner/UNC-Chapel Hill)

Quick shifts

Even before the campus went fully remote, the University Libraries was preparing to meet the needs of students and faculty who would soon be dispersed around the world.

“We started very quickly to think about how we would maintain access for students. How were we going to get them what they needed?” recalls Nerea Llamas, associate University librarian for collections strategy and services.

The concern for students was acute because of the way they tend to use the libraries, often hunting for sources right up until a project is due or settling down in the Undergraduate Library with a stack of reserve reading.

Library staff went to work with faculty to figure out what students would most need in order to complete assignments, and then they integrated those items into course websites. On the way out the door, staff scanned and added hundreds of pages to electronic reserve readings. They also sought out e-books and streaming media to take the place of items that would otherwise require an in-person visit.

A parallel shift took place in library instruction. During a typical semester, librarians visit classes to teach research techniques—introductory overviews for first-year students, and subject-specific deep dives for advanced classes and graduate students. Like almost everyone else, librarians turned to Zoom, honing techniques for online teaching and developing meaningful exercises for the virtual environment.

“There has been a lot of acceptance of virtual instruction,” says Llamas. In some cases, it has been even more effective than in-person encounters. “For some students who may be hesitant to talk to the librarian or to follow up, there’s evidence that the virtual environment breaks down barriers. They will contact the librarian more readily because they can do it virtually and have already interacted that way.”

The digital sessions have been so successful, says Llamas, “that I don’t imagine we’ll ever fully go back to in-person instruction or consultations.”

Increasing access to online resources also helped faculty and research personnel with their ongoing work as the campus closure wore on.

During the spring, many publishers temporarily lifted paywalls on e-books and journals. The largest infusion of electronic content came from the HathiTrust Digital Library, a shared repository to which many libraries, including UNC-Chapel Hill, contribute books they have digitized. The University Libraries opted into Hathi’s Emergency Temporary Access Service. This step gave Carolina students and faculty access to more than 1.1 million books from other member libraries—the digital versions of books that were otherwise locked up in Chapel Hill’s closed library buildings.

“We heard from a number of faculty who were thrilled to have the Hathi content available to them and have written to us saying, ‘this is an amazing service,’” says Llamas.

At the same time, the University Libraries has expanded its purchases of electronic books and streaming media, adding several thousand titles over just a few months and subscribing to services such as OverDrive, which package many e-books and audiobooks together for libraries.

For researchers and readers who need or prefer a physical book, the Library stood up a no-contact pickup program. Library staff members pull books from the shelves and have them ready for pickup at Davis Library or the Health Sciences Library, the two library facilities open to the public. Once a week, staff also deliver books outside for readers who prefer not to come into the building.

Joe Mitchem, assistant head of Davis Library Circulation, readies books for curbside pickup. July 28, 2020.

(Jon Gardiner/UNC-Chapel Hill)

In October, the Library took the additional step of offering a books-by-mail service to UNC-Chapel Hill students and faculty, along with community borrowers in the Triangle.

“In the past, we provided a mail service for distance ed students,” says Joe Williams, director of public services. “This semester, virtually everybody is distance ed. We know what a difficult time this is. People haven’t wanted to be out and about and sometimes they cannot be. Between the pickup service and the mail service, we are trying to make it as easy as possible for students and faculty to get what they need.”

Special collections superheroes

Connecting researchers with library materials has posed unique challenges for the staff at the Wilson Special Collections Library. Wilson Library, which is home to rare books and one-of-a-kind archival documents, closed its doors to the public in March and reopened for staff only at the end of June.

“The library building closed, but we stayed open,” says Jason Tomberlin, head of research and instructional services at Wilson Library. “We’re still responding to hundreds of emails. We’re still doing Zoom consultations.”

Despite the pandemic, Wilson Library draws inquiries not only from Carolina researchers, but from around the country. “In the last week alone, I’ve had inquiries from the University of Wyoming, one from Yale and one from somewhere in Alabama,” says Tomberlin.

During the first months of the pandemic, Tomberlin and his colleagues pointed people to the web, where they could consult hundreds of thousands of items that the University Libraries had digitized and shared online over more than two decades. Still, this represents just a fraction of what is available to in-person visitors.

Since June, scanning staff have been back at work, making copies of everything their equipment will allow in order to help researchers and support instructors who teach with special collections materials. This includes “books, documents, photographs, negatives, maps, VHS tapes. Just about anything that we have in the building,” says Tomberlin.

Taylor de Klerk, Wilson Library’s research room manager, has helped to organize the incoming requests and make sure that researchers get what they need.

“We’ve been calling it a virtual research room,” says de Klerk, “but we’ve had to reframe what it actually means for us to do reference work.”

Usually, says de Klerk, reading room staff largely retrieve and deliver requested items to people. “Now, it’s more hands-on,” she says. “Sometimes we need to do the research for people” by looking at how collections are described to see what the researcher really wants, or paging through folders for just the right document. “We have to put ourselves in their shoes a little more.”

Even when the staff cannot digitize everything a researcher needs, people are grateful. “We’ve had people tell us it’s like Christmas morning when they get their scans. Somebody called us superheroes,” says de Klerk.

Not everything translates to the digital environment, says Tomberlin. “Special collections are still very tactile. What does that book look like? What does it feel like? Looking at the book, examining it—it’s just hard to do online.”

For de Klerk, it’s the personal element that is missing. “Just being able to see people and interact with them as they do their research, see them discover things and have their questions answered, is really rewarding,” she says.

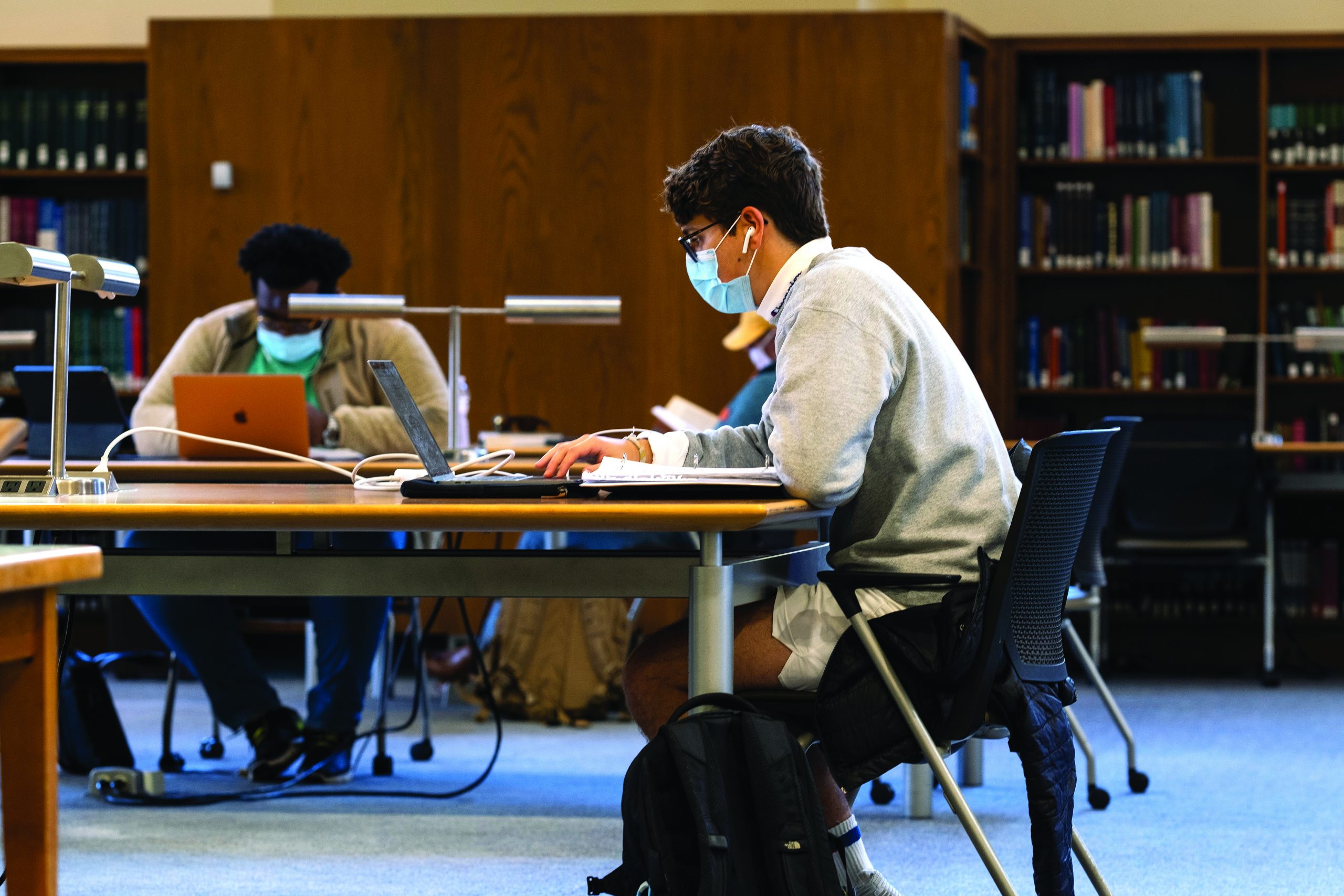

Students study in Davis Library on the campus of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. November 19, 2020.

(Jon Gardiner/UNC-Chapel Hill)

The future is “digital first”

Even after the University returns to normal operations at some time in the future, the pandemic has likely changed library services forever. It has also illustrated their value.

“2020 was a rough year, and we have a responsibility to become a stronger organization,” says Vice Provost for University Libraries and University Librarian Elaine Westbrooks.

Westbrooks points to the high levels of virtual use that the University Libraries has received throughout the pandemic as evidence of this imperative.

In the time ahead, she says, not only will many people remain dispersed, but “we are going to have students who are in an even more precarious situation than they were before. There are a lot of students who are not going to be able to afford their books. We are going to be a safety net for people” as they continue working and learning in a transformed environment.

“When times are hard, libraries get used a lot more,” says Westbrooks. “Libraries become critical infrastructure for people to survive—not just thrive but survive.”

To prepare for this future, the University Libraries has begun referring to an emerging “digital first” strategy—a way to deliver library resources and assistance to people efficiently and regardless of their location.

Tomberlin and his colleagues across the library system have been talking about creating videos or online teaching modules to provide the library introductions and overviews that normally take place in-person dozens of times a semester.

“Liaison librarians can’t always be in the classroom to give that 5-minute or 10-minute or 30-minute talk,” says Associate University Librarian Llamas. “The pandemic has given them an opportunity to start experimenting with new ways of doing things and to see that they can be successful.”

Alongside the shift to virtual teaching, the pandemic has accelerated the shift away from print and toward the purchase of e-books and journals. Staff have also sped implementation of alternatives to owning materials, such as by purchasing individual articles to send to researchers, rather than subscribing to entire journals. And print reserves, says Llamas, “are going the way of the dinosaur.”

The ramifications will cascade. More electronic content will require more specialists who can negotiate licenses and integrate digital publications into the Library’s online environment. The shift to online teaching will call for new expertise in digital pedagogy and peer-to-peer training, as well as an intensified emphasis on digitizing special collections materials.

Whatever the future may hold, one other lesson that will endure is the knowledge that, when it mattered most, employees stepped up to continue providing services under the most challenging conditions.

Front-desk staff “have not for one second hesitated to come into the building and do the work that needs to be done,” says Llamas. “They have given of their time in a way that has never been asked of them.”

In fact, across the organization, says Llamas, employees “have stepped up and volunteered. They have dedicated themselves to transforming the way we did things in March and then again as we reentered in July and August. I don’t think I’m surprised, but I will say that this experience has reaffirmed how very dedicated and able our staff is.”

Health Sciences Library

During a pandemic, reliable health information is more important than ever. In 2020, the staff of the Health Sciences Library had many opportunities to put their unique expertise to work.

For example, when the School of Medicine developed a month-long COVID-19 curriculum in the spring for more than 400 medical and physician assistant students who couldn’t report for clinical duties, Sarah Wright stepped in.

Wright, head of clinical and statewide engagement and School of Medicine liaison librarian, created a 30-minute video module. It explained how to search the rapidly evolving medical literature for up-to-date information about the virus. Wright also helped students in a newly formed elective to conduct research about the history of pandemics in society.

Meanwhile, HSL librarians created on online guide to COVID-19 resources; it had received more than 23,000 views by fall. They also fielded questions from around the state and the country.

For example:

- What are the Medicaid coding changes for COVID-19?

- What is the CDC guidance for health care professionals in high-exposure situations?

- What are the guidelines for cleaning health care facilities?

- What is the appropriate documentation for telehealth appointments?

- How effective are 3D-printed face shields?

- What does the literature say about screening COVID-19 patients for future complications?

- Are there videos that show proper techniques for donning and doffing protective equipment?

- What is the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of health care workers?

To learn more about the Health Sciences Library, which celebrated 50 years in its current location in 2020, see the spring 2020 issue of Windows.

Story by Judy Panitch

This story originally appeared in the fall/winter 2020 issue of Windows, the magazine of the Friends of the Library at the University Libraries.

Return to Windows fall/winter 2020 stories